The 7 Keys of Discovery

Keys

Giant rock formations

Giant rock formations Geology

Geology Panoramic views

Panoramic views Traces of Life

Traces of Life Flora

Flora Martel Exploration

Martel Exploration Fables and Legends

Fables and Legends

7 themes to suit your preferences and guide you through the Cité de Pierres and give you the essentials.

The site is near to Millau and is one of the most beautiful tourist sites in the Aveyron. An outdoor activity that can be done with your family, in groups or individually.

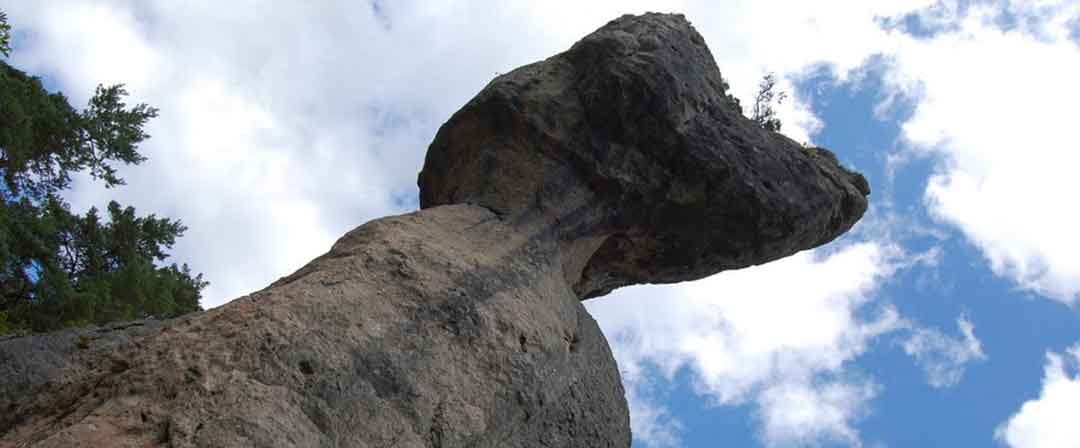

Giant rock formations

30 unique and monumental works of natural art

30 unique and monumental works of natural art

While geological forces were shaping the layout of the Cité de Pierres, the slow work of sculpting the city’s monuments was occurring deep inside the rock.

Due to its origins, this rock contains naturally-occurring crystals resistant to the attack of water. Through cracks or the rock’s porosity, water can penetrate the rocks and continue eroding. Layers made of large crystals are disaggregated more quickly and intensely, forming rounded, hollow shapes. Those made of thinner crystals are more resistant and form overhangs and entablatures. The dissolved elements form a sand which is washed away by the water, giving way to cavities and shapes of all kinds. Surface erosion adds the final chisels, sculpting the extravagant giant stones and creating natural, unique and monumental works. There are many natural rock sculptures (Roc’Art) on the site. Over 30 of them have been listed because they are visible and accessible from viewpoints and trails.

The Giant Rock formations of the Cité de Pierres, are among the most impressive rocky monoliths to be seen around Millau. Discover the city through its 30 natural works of art: La Cuidad, Le Douminal, La Brèche de Rolland, Roc du Corridor, Avenue du Corridor, L’Amphore, L’Oule, La Cathédrale, La Grande Nef, L’Éléphant, Les Remparts, Le Grand Sphinx, La Quille, L’Avenue des Obélisques, La Porte de Mycènes, Le Crocodile, L’Arc de Triomphe, Le Roc Camparolié, Château Gaillard, Roc de la Lucarne, L’Escarpe, La Chaire du Diable, Le Trou de La Lune, La Tête de l’Ours, La Reine Victoria, L’Allée des Tombeaux, Le Sphinx, La Chaise Curule, La Poterne, La Tête d’Arlequin.

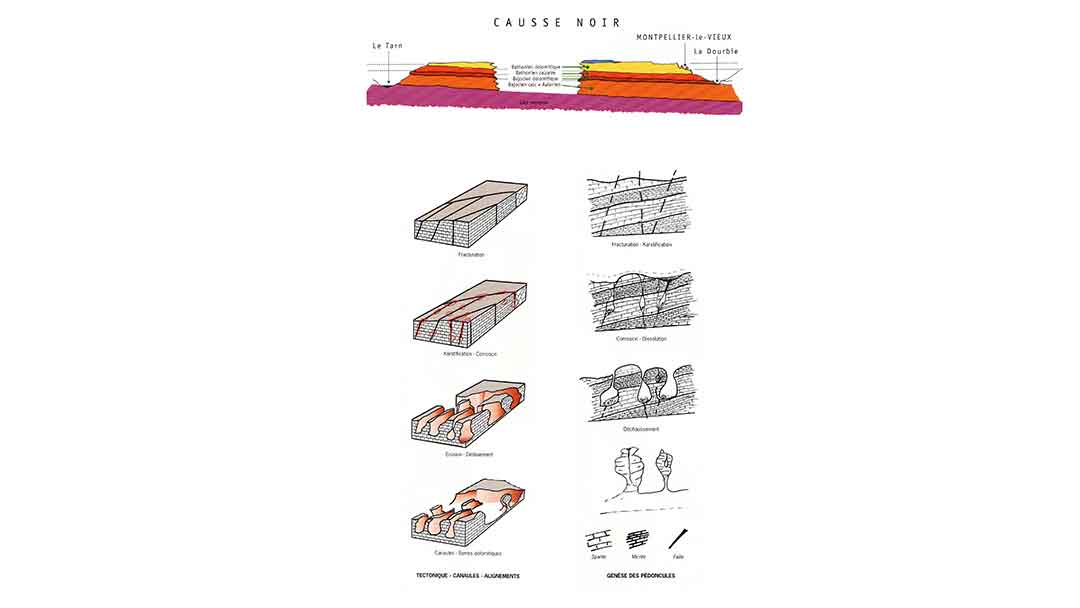

Geology

170 million years of shaping by water and wind

170 million years of shaping by water and wind

Aveyron’s current geology was formed more than 170 million years ago when the sea still covered the region. During this time there was a tropical climate, and the sea covered what was to become the Causse Noir, similar to the atolls of the Pacific. The warm and deep waters shelter an algae and coral reef in which many sponges, molluscs, sea urchins and crustaceans thrive.

The remains and skeletons of these organisms fell to the seabed until a 300-metre thick limestone layer formed from these remains settling at the bottom of the ocean.

A 100 million years ago: The Alpes and the Pyrenees are starting to form. At the bottom of the ocean the rocks endure extreme forces. The limestone layers resist, bend and eventually fracture. These fractures then create parallel faults, similar to the crevasse and serac fields that we can see on glaciers today.

20 million years ago, the Grands Causses formation is getting steadily higher, with the sea having disappeared from the region.

Risen slowly and strenuously from the bottom of the ocean, the limestone rock made up of sediments of marine organisms is webbed with scars making it less dense and more permeable. Water can circulate through these cracks, starting the corrosion of the Causse Noir. The actions of these elements make the existing passages wider and transform them into roads, passes, walls and circles creating the architectural layout of the Cité de Pierres.

In order to understand and observe Aveyron’s fascinating geological history in the heart of the Causse Noir, the Cité de Pierres offers 10 staggering viewpoints overlooking the Causses and the Dourbie gorges. You can visit the Cité de Pierres at Montpellier-le-Vieux in many ways – find out how to come and explore the city

Traces of Life

Rock shelters and sheepfolds

Rock shelters and sheepfolds

La Cité de Pierres is an integral part of Aveyron’s history. It was inhabited continuously from the Neolithic period (6000 – 3500 BC) in the Middle Ages, to the Iron Age and the Gallo-Roman period. The most visible or accessible traces of life are the rock shelters, cisterns and sheepfolds that are evidence of agricultural activity from the early Neolithic period.

The Gallo-Roman period and the early Middle Ages were marked by intensive exploitation of the forest: cutting wood for heating the pottery of Millau and distilling resin from the branches of the conifers to produce the pitch necessary for waterproofing the hulls of ships.

However, the most unusual traces can be found on the terraces at the tops of the large rocky areas. These allowed their inhabitants to be safe from predators, and to serve as a place of solar or lunar worship, above the sculpture “le Trou de la Lune”.

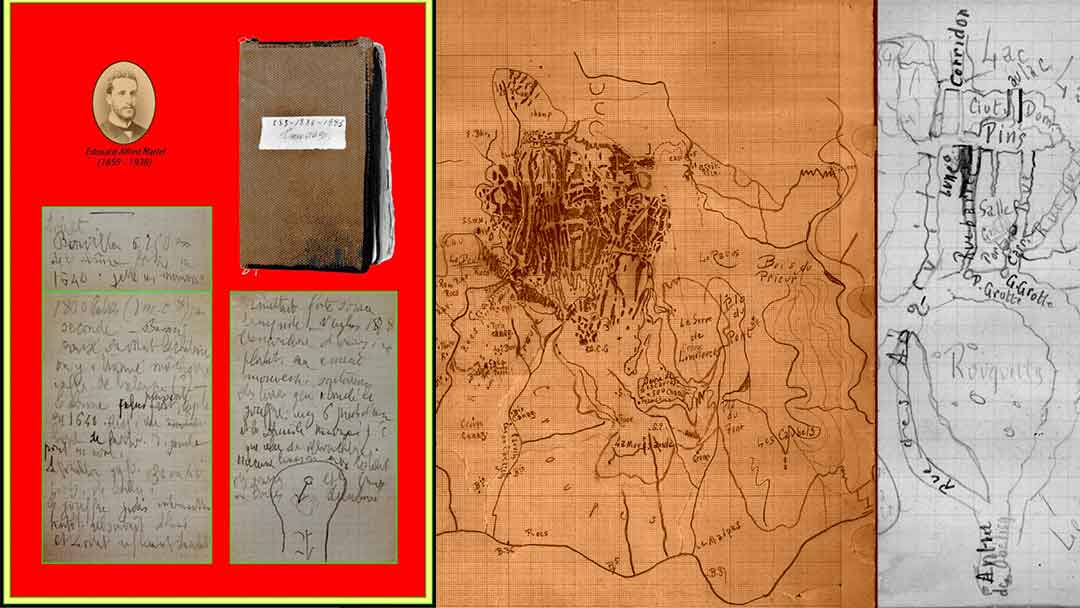

Martel Exploration

An extraordinary adventure

An extraordinary adventure

At the end of the Middle Ages, the Cité de Pierres in Montpellier-le-Vieux was a closed-in and mysterious site which gradually fell into oblivion. In 1884, Mr de Barbeyrac, a land-owner of the Causse Noir region, decided to explore the area with the help of Mr de Malafosse, president of the Société Géographique de Toulouse. After an initial visit they decided to invite, in spite of his young age, the 25 year old Edouard Alfred Martel, who was already well known for his discoveries in the Tarn gorges.

In 4 days, from the 11th until the 14th of September he explored la Cité de Pierres completely and became enthusiastic about this new “Pompeii”, this “Acropolis of the Cévennes”.

The following year, in 11 days from the 2nd to 13th of September 1885, he carried out a 10,000-scale survey for the first map of the Cité de Pierres.

A genuine adventure using the means available at the time

The Société Geographique de Toulouse and the French Alpine Club published a number of articles.

In early 1886, the French Alpine Club decided to add its support to forging the first access pathways through the site.

Guides were then able to show the Cité de Pierres to a few privileged visitors, setting out from the village of La Roque Sainte Marguerite at the bottom of the Dourbie Gorges. They took the first visitors up on mules and the round-trip expedition took a full day.

At the same time, Mr Armand Viré began archaeological research on the site to establish its history.

In 1938 the Société de l’Aven Armand (founded by Edouard Alfred Martel in 1897) opened an access road to Montpellier-le-Vieux from the hamlet of Maubert.

The Cité de Pierres then experienced significant tourism development.

Many were involved in discovering and promoting the Montpellier-le-Vieux and Cité de Pierres sites, but it was Edouard Alfred Martel who was the driving force, using all his talents as an explorer to cope with the technical difficulties faced at the time.

Panoramic views

Breath-taking views

Breath-taking views

The Cité de Pierres is on a promontory nestled on the edge of the Causse Noir and overlooking the Dourbie Valley. From its many breath-taking viewpoints, you can discover the city in its entirety with its fantastic tangle of alleys and ramparts, its towers and monumental bastions, its circuses and mysterious ravines. There is also a 360° panoramic viewpoint of the surrounding area of the Grands Causses, as far as the eye can see: Larzac, Méjean and Sauveterre.

Depending on the time of day, the seasons and the angle of the sun, a bewitching play of light brings this dead city to life, magnifying its architecture and colours through space and time.

These views, among the most beautiful panoramas of the Aveyron (12), can be seen during your walks, from the mini train, during a via ferrata expedition, an adventure game or an Explor’Game®.

Must-see views

Le Belvédère, La Chaire du Diable, Le Magnifique, Les Remparts, La Quille, Le Douminal, L’Observatoire, La Terrasse, La Ciudad, Le Trou de la Lune.

Flora

Plant species and flowers of the Causses

Plant species and flowers of the Causses

A multitude of varieties thanks to the crossing of Mediterranean and mountain climates.

Contrasting with the aridity of the Causse, the Cité de Pierres is a prime area for vegetation. The flora of Aveyron, and more particularly that of the Causses, is very diverse (you can find nearly a third of the plant species of France here). In the Causses, the shelter from rocks and variations in exposure have favoured the development of this particular vegetation. We have therefore listed here only a few of the most characteristic and easily identifiable species.

Tree vegetation

Scots pine: It is the main natural species of the Grands Causses. Undemanding, it clings to the rock pushing its roots into the cracks, a real “bonsai” often decorating the top of the rocks.

The beech tree: Uncommon at this altitude, but comfortable with the limestone soils, beech is nevertheless more delicate and looks for humid shaded areas where fog is frequent.

The white oak or pubescent oak: Accustomed to dry and limestone soils, it is a very common tree in Aveyron’s flora. It can be found on ridges as well as in ravines. Its deciduous leaves with their characteristic white down dry on the tree in autumn but often fall only in spring, under the pressure of buds.

Hazelnut: It is very common in sheltered areas and particularly at the foot of large rocky massifs.

Sorb tree: This species, characteristic of the Causses, spreads the foliage of its silvery leaves in summer and grows succulent berries in autumn.

The shrubs

Boxwood: A very common species amongst the flora of the Aveyron, boxwood is found everywhere in thick, glossy bushes. The nectar of its flowers is highly sought after by bees.

Juniper: Almost as frequent as boxwood, particularly comfortable growing on the Dolomites, junipers plant their thorny cones everywhere, encasing the delicate berries that thrushes love….and also seen in local cuisine.

Saskatoon berry: In May, the white flowers of these common shrubs make it seem as though there has been a recent snowfall depending on the lighting they receive.

Dogwood: Common under oaks, this shrub produces white flowers from May to June, followed by large, shiny black berries that wild boars love.

Bearberry: This small shrub covers the ground in a thick, bright green, leafy carpet, and is covered with large red berries at the end of the summer. In spring, one can see delicate little bells on the shrub.

Still classified as shrubs despite their bushy tuft-like appearance, thyme, lavender and dorycnium scent the air of the area with their fragrant flowers that give the honey of the Causses so distinctive.

The flowers of the Causses

Every spring, the flowers of the Causses open-up their petals. They add colour to the grass, with dots of the delicate purple of pulsatile anemones with a heart of sulphur or the gold of Adonis. Euphorbias add soft green and yellow touches everywhere.

The asphodels raise their long stems to the side of the slopes, with large clusters of white flowers.

Orchids and ophrys: All types and colours, they are plentiful and easy to find if you know what to look for. In cooler corners, it is not uncommon to find splendid blue bellflowers.

Long-leaved helleborine (Cephalanthera): Later on, the alpine asters with their purple tones flower.

Mountain Anthyllis, white or pink rockroses with crumpled petals and feathers more poetically called angel hair whose long feathery edges fly in the wind like thousands of white plumes.

Finally, the acanthus-leaved carlina, the cardabelle of the caussenards, this “causse rose” spreads its golden rays on the ground from the end of July to September.

Fables and Legends

![]() The Cité de Pierres in Montpellier-le-Vieux has been the subject of many legends and beliefs since antiquity thanks to its architecture with its strange and fantastic shapes.

The Cité de Pierres in Montpellier-le-Vieux has been the subject of many legends and beliefs since antiquity thanks to its architecture with its strange and fantastic shapes.

The old stories about the city are among the most fascinating stories of the Occitan region.

The name

The name Montpellier-le-Vieux is said to come from the travelling shepherds of the Languedoc plains. They would have given it the nickname of their reference city by adding the term “vieux” as a reflection of the ruined nature of this ghost city. In the Occitan language, the nickname of the capital of Hérault is “Lou Clapas” which means “pile of stones”. However, in this language “vieux (old)” is “vielh” (pronounced biel) and also refers to the Devil in the imaginary and wonderful world of folk stories. In fact, many rocks once bore the name of the Devil before Martel renamed them according to his erudite imagination. Thus “The Eye of the Devil” (“L’Oeil du Diable”) (today “La Porte de Mycènes”) and also the whole site which was once called “La Cité du Diable” (“The City of the Devil”). In the Middle Ages in Occitan, history often attributed the gigantic works to satanic beings or giants. “Lo Clapas Vielh” also came from “Lo Clapas del Vielh” (The Devil’s Stones). But finally the underlying origins come from the notions of City and Stones and therefore it became “La Cité de Pierres” (“The City of Stones”).

The Fairies

Another legend says that la Cité de Pierres sheltered three fairies from the southern garrigues to escape Mourghi, an evil spirit who wanted to harm them. Amy the thoughtful, Amyne the dreamer and Benjamin the joker arrived one evening in May. They very quickly built a citadel with ramparts, streets, palaces, bridges and squares. To complete the scenery, they planted pine trees, some oak trees, and a lot of wild grasses and wildflowers. All of this was a world of entanglement in which Mourghi, despite being cunning, became lost and so gave up his hunt. Then began a long period of peace, happiness and quiet joy for the fairies. But little by little the nostalgia for the garrigues became too strong and they returned near the sea and the sun. The city then fell asleep in their absence. Then, undoubtedly summoned by some devil, the wind, rain and snow raged through the now dead city. The fairies left but their memory still lives in the city. The song of the birds, the sound of the wind, the bells of the herds, the echoes of Benjamin’s laughter. This tree with its tortured trunk on the edge of the precipice, the image of the evil Mourghi. And this strange atmosphere, the image of Amyne’s dream. The fairies are still there, masters of dreams.

A legendary film: “La Grande Vadrouille”

One of the iconic scenes of Gérard Oury’s legendary film, released in 1966, was shot at la Cité de Pierres. The scene in which Bourvil carries Louis de Funès on his shoulders and which had the honour of being the film’s poster. The shots were taken at the Roc du Corridor (4), then at the Ramparts (20) and finally at the Porte de Mycènes (17). Originally the scene was planned differently, but on the morning of the shooting Louis de Funès suggested that Bourvil get off the wall onto his back and hit his helmet. This scene called “et ben dis donc” has become a momentous clip.